Written by Ainsley Meyer.

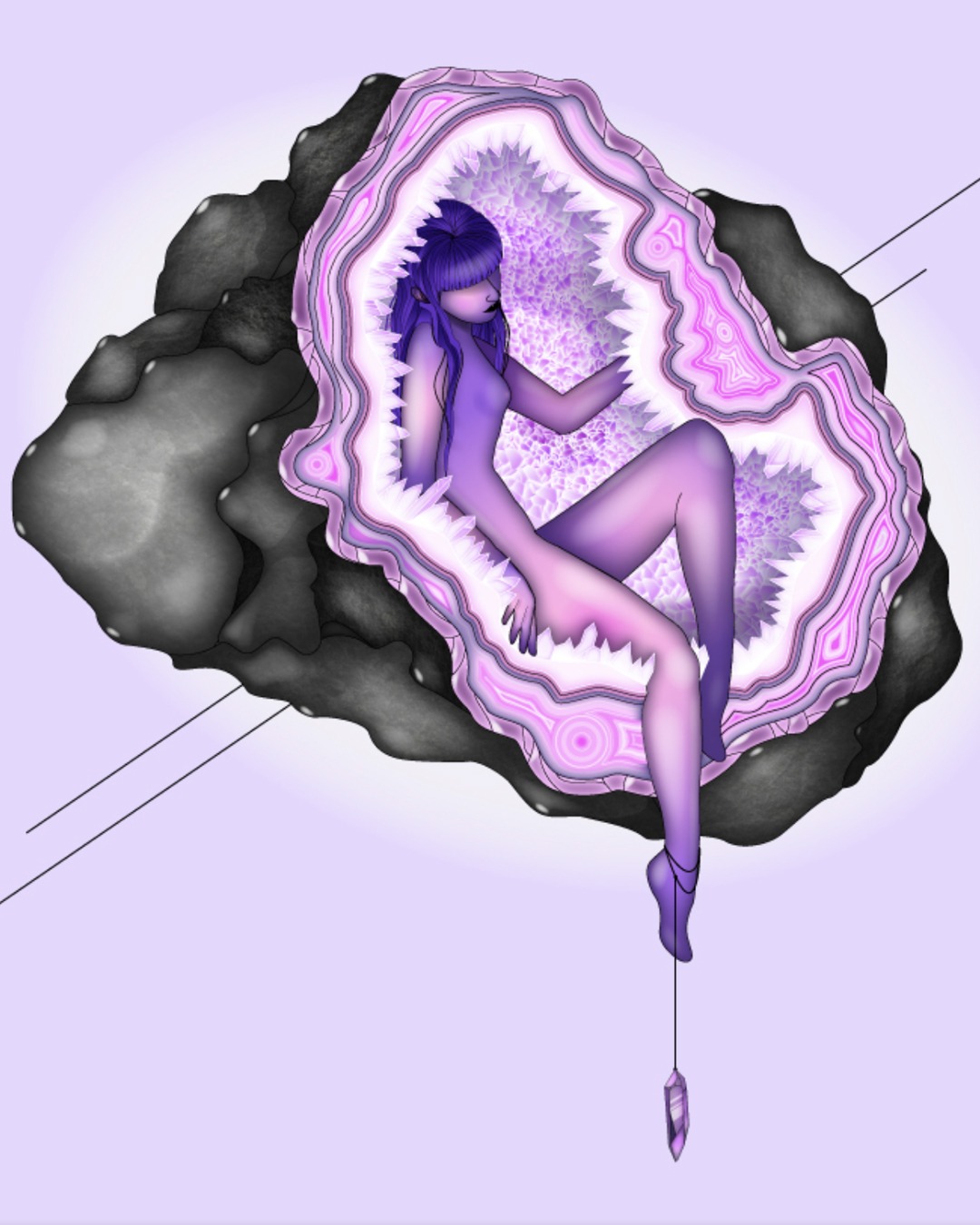

Art by Amrei Hofstätter.

The meeting began as they always do: When was the date of your last period? Never. Are you sexually active? Yes. How can you be sure you’re not pregnant if you’re sexually active? This again?

I shyly broached the subject of how painful some sex was. Is it always that way? I asked. She hit me with a not-so-subtle suggestion I delay sex until I was older. Then she propped my legs up in stirrups and began the exam. I felt a sharp, searing stab.

Please stop! It hurts! I begged through a clenched jaw.

But she kept going.

“If you’re old enough to have sex” she lectured, “you’re old enough to deal with this”. She was rough with the speculum.

I was fifteen, but this sort of hurt wasn’t new to me.

At that age, I’d regularly be struck by unexpected episodes of pain. These left me glued to bathroom floors, sweating and writhing, clawing at my lower stomach, and wishing I were dead. But I was lucky when this happened at home, in private- some days I’d find myself passed out in gyms, or on sidewalks, or stifling screams in my school’s nurses office.

I was fifteen, but this sort of hurt wasn’t new to me.

No number of visits to the doctor seemed to help. One even suggested that, if I was going to be skipping school, I should come up with better excuses. And, if I was trying to get a prescription, I could forget about it. That was about all they had to offer, no real clues as to what was happening inside my body.

I lived in a constant state of uncomfortable inhale, waiting for pain to strike, knowing I wouldn’t be understood or believed when it did.

Flash forward a few months and I’m laying on a table, cool jelly smeared across my lower abdomen. A doctor had reluctantly ordered me an ultrasound. As they slid the probe over my skin, the doctor went silent. She looked at the nurse, making a gesture I didn’t understand. The nurse left, returning quickly with a second doctor. Their eyes flicked nervously between the screen, my face, and my mother.

“We need to schedule surgery as soon as possible”.

So instead of having periods, months and months worth of blood sat, pressing against the wall of tissue, with nowhere to go.

The doctors discovered I’d been born with a “transverse vaginal septum”, something extremely rare. About one in thirty thousand people are born with it. Some people call it a, “dead-end-vagina” (who even comes up with these names?). Basically, I was born with a wall of tissue which separated my vagina from the rest of my reproductive organs. It also happened to block the uterine lining from exiting my body. So instead of having periods, months and months worth of blood sat, pressing against the wall of tissue, with nowhere to go.

I wasn’t explained much before or after the surgery. They cleared the wall so I could menstruate the way most people do, and then sent me on my way. They didn’t test my chromosomes, or hormones, though I’ve read people born with a transverse vaginal septum often have other bodily characteristics which defy the sex binary.

I was bedridden for a month afterwards, and had what I can only describe as the never ending period from hell. I missed a month of school and couldn’t tell anybody why. I was scared, and embarrassed. Nobody walked me through what this all meant, or how my life would look like going forward.

What they meant was, I was now able to menstruate and could maybe have kids one day. My vagina suddenly had a purpose. But, being in significant pain all the time is not normal.

Doctors assured me everything was, “normal now”. I question what this means? I have other reproductive health disorders which cause me chronic pain. Is pain this frequent “normal”? What they meant was, I was now able to menstruate and could maybe have kids one day. My vagina suddenly had a purpose. But, being in significant pain all the time is not normal.

And what if they hadn’t done that ultrasound? Would my uterus have ruptured from the pooling of blood? For what reason- because when we say we’re in pain people don’t believe us? Because everything externally seemed the way they’d expect it to be?

I looked “normal” on the outside, to them. I have a vulva, and vagina, so it was assumed everything on the inside was situated in the very binary way so many doctors associate with, “female”. This closely held notion harmed me as a teenager, and continues to hurt me and so many others.

Visits to the gynecologist are clunky, awkward affairs charged with fear and uncertainty. I once watched a doctor google what a “transverse vaginal septum” is.

As an LGBTQI+ person, I’m excluded from so many conversations surrounding reproductive health. Visits to the gynecologist are clunky, awkward affairs charged with fear and uncertainty. I once watched a doctor google what a “transverse vaginal septum” is.

I’ll never be able to go to a gynecologist and feel safe, or understood. And this in itself is, at its core, also a reproductive health issue.

I urge you to rethink reproductive justice, and binary thinking. Reproductive justice isn’t just about Roe vs. Wade (though Roe vs. Wade is important), or whatever politician has most recently threatened it.

It’s about the subtle ways we’re denied the time, care, and trust needed from our healthcare providers to keep a body healthy. It’s about all of us who don’t fit into the very narrow scope of who these systems were and are designed to serve.

I wasn’t born with a, “dead end vagina”. I simply have the body I was born with, and it wasn’t what doctors expect. And that’s okay.

About The Author

Ainsley Meyer is a queer writer living in Seattle. She has a day job that keeps her very tired but does her best to write, make zines, take photos, and create, in her free time.

Follow on IG: @avalanchewords