Written by Rebecca Fontenot.

Me getting pregnant in my late teens was a surprise to everyone that knew me, for a number of reasons:

- The father was surprised because we always used condoms, and because when one had broken, I’d shelled out the requisite $40 for a morning-after pill.

- My friends were surprised because the father and I had broken up about a year before and I hadn’t told anybody we were still fucking.

- My parents were surprised because they believed that, having graduated high school at the top of my class, I was too smart to do a monumentally stupid thing like get knocked up.

So a smart half-Korean cookie like myself is the last teen anybody expected to wind up pregnant, but the short version is this:

The father and I dated for three years, through high school and a bit of college, before our relationship descended into stunted discontent and we agreed to go our separate ways. I was more ready for the split than he was, and, in efforts to soften the blow and help him come to terms with the break-up, I stuck around for a long time, accepting his “I still love you”s and, occasionally, his embraces. Sometimes I told him I just wanted to be friends. Sometimes I said not today. But one way or another we would end up in the bedroom again and again, and I just didn’t have it in me to refuse every time. I was so used to his body. I wasn’t seeing anybody else. I couldn’t think of a good reason to say no.

In Korean culture, youth always gives way to age. I grew up in a strict hierarchy where my mother’s word was law, and the kind of law that brooks no argument, question, disobedience, or “disrespect” in any form.

Of course now, any number of excellent reasons to refuse come to mind. My body my rules, for one. Now’s a bad time for me to get pregnant, for another. But I wasn’t thinking about myself, really. That’s my upbringing at work.

In Korean culture, youth always gives way to age. I grew up in a strict hierarchy where my mother’s word was law, and the kind of law that brooks no argument, question, disobedience, or “disrespect” in any form. Barring my mother’s presence, the next-oldest family member was in charge, and I was the youngest; nobody needed or wanted my input, so I mostly kept to myself. The perfect model of Korean filial piety, I didn’t cause any trouble and tended to everyone’s needs before my own. I grew up always knowing exactly where I stood in importance: dead last.

By the time I got involved with guys and sex, this whole keeping-my-needs-to-myself thing worked against me in two ways. One, it was written deep in my psyche that my job was to put his needs first and endure a bit of pain to take care of him. Two, I knew I could never talk to my family about it.

So there I was, nineteen and holding a white pee stick with the two little pink lines that meant I had a uterus full of embryo, knowing I was about to become the biggest disappointment of my parents’ lives. It was two weeks before I had the time to road trip home from college to tell them the news.

The perfect model of Korean filial piety, I didn’t cause any trouble and tended to everyone’s needs before my own. I grew up always knowing exactly where I stood in importance: dead last.

The reaction was roughly what I expected: from my mother, a lot of “I’m going to kill the bastard that did this to you,” which quickly turned into “You’re so stupid” when I made it clear that the sex had been consensual. From my father, stoic, deeply disappointed silence. I stayed with my sister that night.

In my parents’ defense, they were utterly shocked that their perfect daughter—who had never rocked the boat in any way and who didn’t even have a boyfriend—randomly turned up pregnant. Once they got over their surprise, they supported me, took me in, and helped take care of the baby when he was born. But on the other hand, considering the atrocious state of sexual education in Texas, maybe utter shock at an accidental pregnancy isn’t so understandable.

Before November 2020’s grudging forfeit to common sense, sex ed requirements hadn’t been updated in Texas since 1997 (and these new changes have in fact changed very little). When I was a teenager, sexual education was not a requirement in Texan schools. But if sex ed was taught, it was a state requirement that abstinence be emphasized. There was no requirement for mention of other contraceptive methods. It wasn’t even a requirement that the information be medically accurate. Even after the update, there’s precious little education on what constitutes consent or healthy sexual behavior, with practically no acknowledgement at all of non-hetero sex.

A quarter of schools don’t offer sex ed at all. Almost three fifths of schools teach abstinence only. The rest—a little over 16%—cover abstinence plus. Unsurprisingly, this system does not work. Only half of Texas teens even use condoms during sexual encounters, resulting in the seventh-highest teen birth rate in the nation. My only exposure to sex ed was an optional three week unit in PE when I was twelve, where they taught us that puberty comes with hairy armpits and pubes, that boys my age were making millions of sperm a day, and that abstinence was how you avoid STDs and pregnancy. The program was called Worth the Wait.

I was never taught that condoms, even used faithfully, will fail one out of every five to ten women; I was never taught how to use any other birth control method. Is it really such a surprise that I got pregnant?

But it’s a powerful illusion that ignoring something will make it simply disappear, and all mention of sex was carefully avoided in my house. Part of it is the traditional Korean ideal that women should exist silently on the fringes, chaste and faithful and supportive to their men; extramarital sex is a major no-no. Another part is that when my mother moved to the US, she became a devout Christian and the paragon of a productive member of society. The “model minority”, the kind no immigrant-hating nationalist could possibly find fault with. Respectable in every way. We half-Korean daughters were expected to uphold the same level of impeccability.

The “model minority”, the kind no immigrant-hating nationalist could possibly find fault with. Respectable in every way. We half-Korean daughters were expected to uphold the same level of impeccability.

Of course, that same horror of appearing anything less than ideal made my mother turn around and support me wholeheartedly once she got used to the idea of me having a baby. If there was no denying the pregnancy, she might as well act like the whole thing was her idea and roll with it. She would pay for everything. The baby and I must live in her house, rent-free. Generosity was the name of the game. And woe if I ever wanted to do something myself or made the slightest appearance of ingratitude. I had ruined myself, after all. Now it was my job to shut up and let someone more capable clean up the mess.

I spent a long time believing this—that I was ruined. That by my own stupidity I had forfeited my right to self-respect. That I had no choice but to sit meekly by and accept emotional abuse from my benefactors. Judgment and shame were my constant companions, because society loves to tread on penniless teenagers who have the audacity to get pregnant. Once you’re married, a baby is a miracle. When you’re a single teen, it just means, “You had sex, you filthy little slut.”

It took me a long time to learn that having a baby didn’t mean that my life was over. It was American society and my Korean upbringing whispering in my head that a woman’s worth is dependent on either her virginity or her husband, and that having neither, I was worthless.

It took me a long time to learn that having a baby didn’t mean that my life was over. It was American society and my Korean upbringing whispering in my head that a woman’s worth is dependent on either her virginity or her husband, and that having neither, I was worthless.

It’s so important to realize what narratives are going on inside your head. As soon as it dawned on me that I was letting misogynistic bullshit rule how I felt about myself, I realized how absurd it was. Anybody that tries to judge me these days finds a much less pliable receptacle than I was when I was nineteen and hated myself.

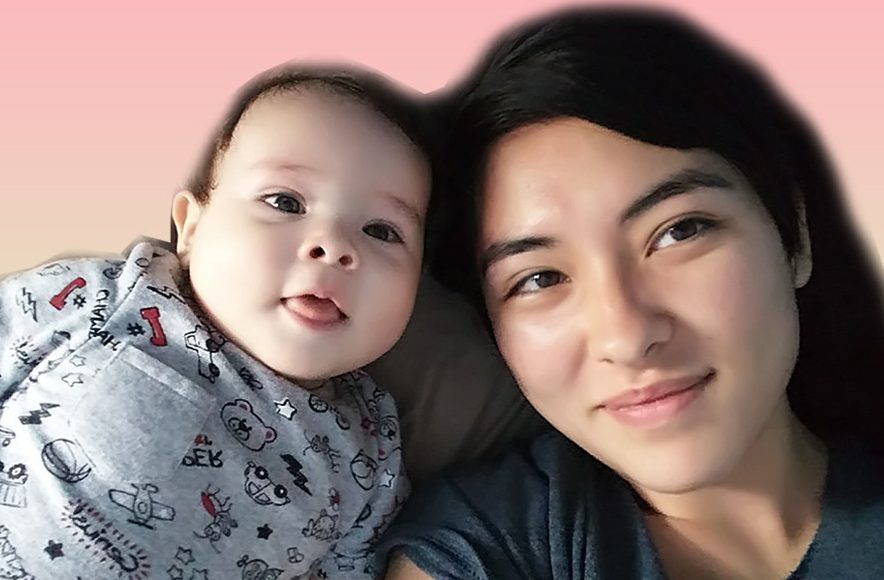

Nobody is worthless. I’m certainly not. I’m a grad student, the primary caretaker of my toddler, and the sole provider of our little family. I may struggle to pay the rent, but I’m doing it, dammit. I’m the mother of a fantastic two-and-a-half-year-old who knows some of the lyrics to Hamilton, who can count to five in three different languages and always tries to put off bedtime for one more minute so we can read one more book. He holds my hand and asks me to sing him to sleep, and every now and then he pats me on the head and says, “You’re such a good Mommy.”

Nobody can tell me I’m ruined.