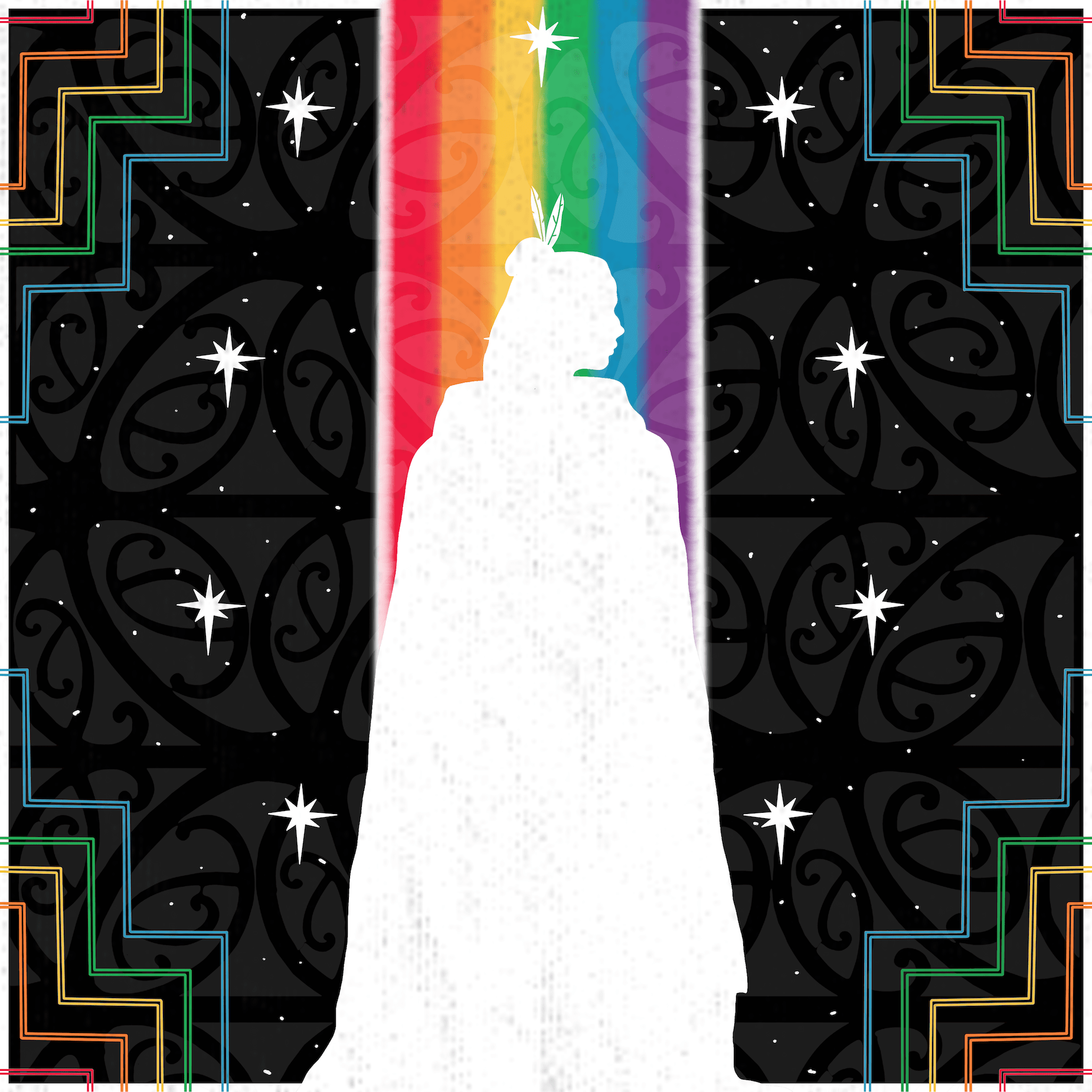

Written by Catalina Benjamin.

Art by Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho.

Growing up in Aotearoa (New Zealand), I was immersed in Māori culture and ideals. Most of the people within Māori culture, similar to other BIPOC communities, find gender and sexuality, taboo. I believed, like the majority of others in NZ, that heterosexuality and being cisgender were the norm and that they were the only correct way to live.

During pre-colonial times, Māori society held particularly open-minded views in regard to sexual fluidity.

When I was 12, I discovered the terms Lesbian, Queer and Gay and I thought “what do those words even mean?” so, I started to research. I learned about the infinite types of sexualities and genders that exist. Surely if they existed this meant they were real and valid? I began to question whether or not I was a member of the LGBTQ+ community, one thing I knew for sure is that I was different. I just had no clue in what way. I went straight to my mother to attempt to find the answers to the questions I so desperately had. She told me that it was normal to question my sexuality, but I was too young to know and that I should wait until I was older and had more life experience to discover what my sexuality was. She was not alone in being sceptical about sexuality, as it is common across Māori culture to be ignorant of and repelled by sexualities and genders that deviate from what society believes to be the norm. But Māori have not always held this position. During pre-colonial times, Māori society held particularly open-minded views in regard to sexual fluidity. The concept of Takatāpui (devoted partner of the same sex) was widely practised and accepted across the various iwi (tribes) in Aotearoa. This term has since been reclaimed in the 1980s by Māori members of the LGBTQ+ community. There are people who strongly believe that Māori sexual fluidity did not exist prior to the colonisation of Aotearoa by the British. Though it is clear that the arrival of the British in New Zealand led to the change in sexual and general behaviour amongst Māori and propelled Takatāpui into a negative and deviant light. This was mainly due to the pressure of Christianity and Western views that accompanied the European settlers. This has resulted in many Māori holding similar views about sexuality that are customary in Christianity.

After confiding in certain people, who I thought were more accepting of me, I was outed. I was fifteen at the time and I thought my life was over.

Over the course of the next year, my questions subsided and were pushed further down as I struggled to be ordinary. At thirteen, I attended a Māori and Catholic Boarding School and sexual fluidity continued to be taboo, which strengthened the internalised homophobia within me. Before I had discovered who, I was, girls at school had already decided that I was a lesbian and was obsessed with vaginas. I was bullied because of this assumption and constantly spent my school days reinforcing that I was not a lesbian and how disgusting that was. I did not consider myself a lesbian but that did not matter to anyone. They assumed and therefore I was. With the constant bullying, the questions I had been ignoring began to resurface, and I realised after a long time of deliberation within myself that I was a member of the LGBTQ+ community. I knew I was not a lesbian because I still liked boys and assumed that I was bisexual. After confiding in certain people, who I thought were more accepting of me, I was outed. I was fifteen at the time and I thought my life was over. Everything changed at school and life got a little weird. Some of the girls would just stare and whisper about me behind my back. This hurt more than the teasing because it meant they didn’t respect me enough to be upfront with me. The ideas about sexuality that are held by the Māori and Catholic communities had helped create the views within those who bullied me and within myself to believe that I was not normal and deserved mistreatment.

The idea that I have to hide such an important aspect of myself, yet my heterosexual relatives are able to flaunt their new relationships, without fear of backlash, is disgusting.

The pain and torment that I received all those years has shaped who I am. It has helped me to discover that I am Queer. My sexuality is fluid and I am who I am regardless of what other people believe to be valid. I still struggle with my sexuality occasionally due to the conflicting views between myself and my culture. My extended family tend to have modern Māori views on sexual fluidity and hold a heteronormative outlook on life. While my mother supports me as much as she can, she believes that I should keep my sexuality a secret until I am in a serious relationship, in a bid to protect me from the predominantly homophobic values of my relatives. The idea that I have to hide such an important aspect of myself, yet my heterosexual relatives are able to flaunt their new relationships, without fear of backlash, is disgusting. It is almost as if I have two versions of myself, which I think I uphold more so for the sake of my mother. The Catalina in Australia who is out and proud about her Queer identity and the Catalina at home in Aotearoa who is quiet about her sexuality and everyone questions if she is a lesbian behind her back. I have been blessed with a loving and accepting mother who has taught me that who I am is valid and that I have the right to be happy regardless of what anyone else believes. I try to educate my family as much as I can that sexuality and gender is not a choice, and that everyone deserves to live as their true selves.

The views of a person who is Māori and LGBTQ+ may conflict with the views of their culture in postcolonial times, but it is important that we remember that the views that our ancestors held during pre-colonial times were more accepting of our Takatāpui ways than the views held by Modern Māori. Therefore, these should be the views of which we aspire to, rather than the views of the colonisers of Aotearoa. My experience of discovering who I am within the LGBTQ+ community and the wider Māori societal context, may not be the same for everyone. It may differ from the experience of those living as LGBTQ+ in other BIPOC communities across the world, but we all have one thing in common. That we must persevere through the homophobia, the conflicting views and the ignorance of others in terms of LGBTQ+ sexuality.

About the Author

He ūri ahau nō Ngāti Maniapoto me Ngāpuhi.

I am a descendant of Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāpuhi.

Catalina Benjamin is a Melbourne based musician and is currently working towards her BA with a double major in History and Classical Studies. She is of mixed Māori, Swiss and English descent. Catalina is passionate about working towards the removal of the taboo surrounding sexuality, gender and sexual abuse within BIPOC communities, through the education of the people living within these communities.

Follow on IG: @cvitkoko | Follow on Twitter: @catmousai