Written by Yassmin Abdel-Magied.

Art by Kristel Brinshot.

CW: Brief mention of fatal violence.

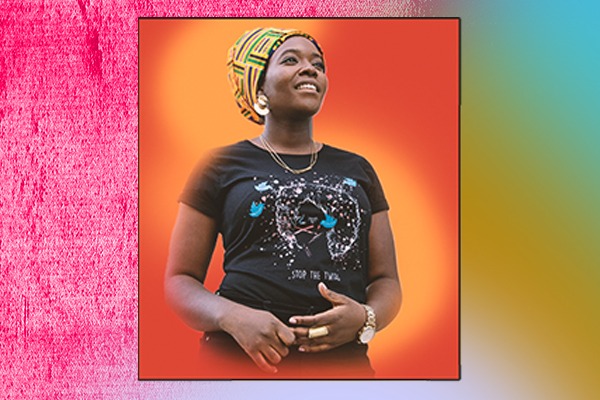

Seyi Akiwowo is the Founder and Executive Director of Glitch, a small charity dedicated to ending online abuse and championing digital citizenship. Glitch was founded shortly after Akiwowo, then a politician, faced horrendous online abuse and violence. Using her lived experience and valued expertise, Akiwowo travels the globe developing practical solutions with governments, NGOs, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and tech companies to protect our public spaces online from hate and abuse. Akiwowo was selected as Amnesty International’s Human Rights Defender in 2018, and both Digital Leader of the Year and a Marie Claire Future Shaper in 2019. She was also invited to give a keynote presentation at TEDxLondon. Many of her achievements have been captured in books and international reports.

The following has been condensed.

Tell us about Glitch, and your personal experiences that inspired it.

Glitch started in 2017 when, as a young female Councillor, I faced horrendous online abuse after a video of my speech at the European Parliament went viral. What started as a campaign and anti-bullying message in a local school has developed into an impactful organisation delivering workshops that have reached thousands of young people and women, and raised a generation of digital citizens. Core to the campaign are making sure no women have to deal with victim-blaming language or poor responses from social media companies, and talking about the diversity of experience on the online space.

What have been your proudest achievements with Glitch?

Glitch has achieved major milestones on a shoestring budget. We have:

- developed and disseminated resources, such as our Fix The Glitch Toolkit. The toolkit is key to our scalability and reach — it has been downloaded across the world, by the likes of refugees in Northern England and organisations in Australia and Myanmar.

- reached over 3,500 young people, European leaders, and teachers in the Middle East with our digital citizenship workshops.

- delivered digital self-care and self-defence training to over 300 women in Europe, Africa, and North America.

- earned supporters such as Rosie Duffield MP, former Parliamentary Private Secretary for the Shadow Women and Equalities Minister; actress and activist Emma Watson; and actress and activist Jameela Jamil.

- been recognized by Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other tech companies.

I quickly learned I had a powerful voice, with a rhythm that resonated with people and the directness of growing up in a Nigerian household.

Salty Name Plate Necklace

You were the youngest black female Councillor in East London, at age 23. What led you to engaging in activism formally, through politics?

For many years, I didn’t even know “activism” was the word to describe what I was doing. I quickly learned I had a powerful voice, with a rhythm that resonated with people and the directness of growing up in a Nigerian household. So, I would regularly find myself calling out the unfairness and frustrations others were unable to. Depending on who you were, my inquisitive, loud, and determined nature was either extremely annoying and disruptive or the “traits of a natural born leader.” Me being a young black woman from East London, you can probably guess which one I heard more.

I clearly remember an “activation” happening when my school friend and neighbour Charlotte was stabbed and murdered at a house party. For weeks, though it felt like months, I kept asking why. Why did Charlotte’s murderer think she needed to hold a knife? Why didn’t we have the lifestyle we see on the Disney Channel, Trouble TV, and Nickelodeon? Bear in mind, this was 2006. None of us were given the appropriate trauma response, nor did we have the language to help us unpack our feelings. My own line of enquiry led me to protesting at the steps of the government. It always came back to the officials making policies affecting me, my family, and my community — yet I didn’t hear my lived experience coming from any of those government buildings.

It was then that I embraced the label “activist,” using my voice in various campaigns for education reform, gender equality, anti-racism, and youth violence. (As a true millennial, I proudly included “activist” in my first Twitter bio.) From there, I realised another way to affect change was within the system and seats of power, so I stood for local government in 2014.

What was the biggest lesson you took away from that experience?

That there is a gap between encouraging women (especially women of colour) to stand for politics and equipping them to overcome the barriers that will come, such as online abuse.

Glitch focuses on fixing the negative impacts of technology, but you are still incredibly passionate about engaging with digital platforms. How do you reconcile the positive and negative aspects of tech?

I love the internet and digital technology! That’s why I’m passionate about preventing them from being hijacked and weaponised against already marginalised and vulnerable communities. Technology and innovation should address inequalities, not reproduce and exacerbate them. Online abuse, hate speech, disinformation — these are the glitches that are preventing the Fourth Industrial Revolution from fulfilling its potential.

What is the most pressing challenge that digital technology needs to address?

Championing digital citizenship in order to address the rise in online abuse. It is not the responsibility of the individual or online communities to effectively practice digital citizenship — efforts must be taken by both government institutions and tech companies to ensure individuals can exercise their digital rights, with increased efforts made to protect the rights of those with multiple and intersecting identities.

Government institutions must prioritise digital citizenship education for all. This should include: how to use digital technologies effectively, an understanding of ethics and related law, online safety, access to justice and redress, and advice on related health and safety issues such as predators, digital self care, and digital footprints.

Technology and innovation should address inequalities, not reproduce and exacerbate them.

The government also has a responsibility to ensure that tech companies prioritise digital citizenship through clear roles and responsibilities, accountability, regulation, and investment in education and resources. Tech companies should create technology and platforms that are safe and non-discriminatory for all users. This involves designing online spaces, systems, rules, and tools — including artificial intelligence — that encourage digital citizenship for their users, dedicating adequate training and resources towards digital citizenship, consulting their users, acting transparently and proactively, and implementing robust safety mechanisms.

What do you hope to achieve on a personal level?

I’m dedicating this time to investing in becoming the leader I will be proud of in 10 years. This involves therapy, coaching, podcasts, and books. I enjoy hosting “In Conversation With Seyi,” an intimate and honest moment with pioneering women, and would love for it to flourish. I hope this, plus sharing more “Behind the Glitch” posts on social media, will both help others learn from my many mistakes and inspire future activists and change makers.

I have a weird phobia of writing, but I do wish to write a book one day, and publish a six-part podcast series using embarrassing and hilarious stories to talk about serious topics — like the time I accidentally travelled with someone else’s passport to Brussels to discuss immigration and the refugee crisis, or when I got my period while talking about period poverty in the U.K.

How do you achieve a sense of balance and happiness in what you do?

An important principle I cherish is self-care. Not the consumerist notion of expensive massages and silent retreats — self-care is about identifying, communicating, and respecting boundaries. This applies to digital spaces, too. I created an energy map, which keeps me on track with finding a sense of peace and balance. Energy can neither be destroyed nor created, so where are you transferring your finite energy? What is depleting and what is restoring your energy?

About the Author

Yassmin Abdel-Magied is a Sudanese-Australian writer, broadcaster and award-winning social advocate.

Yassmin trained as a mechanical engineer and worked on oil and gas rigs around Australia for years before becoming a writer and broadcaster in 2016. She published her debut memoir, Yassmin’s Story, with Penguin Random House at age 24, and followed up with her first fiction book for younger readers, You Must Be Layla, in 2019. Yassmin’s critically acclaimed essays have been published in numerous anthologies, including theGriffith Review, the best-selling It’s Not About The Burqaand The New Daughters of Africa.

Yassmin founded her first organisation, Youth Without Borders, at the age of 16, leading it for nine years. Since, Yassmin has co-founded two other organisations and now shares her learnings through keynotes and workshops. Yassmin has spoken in over 20 countries on unconscious bias and inclusive leadership. Her TED talk, What does my headscarf mean to you, has been viewed over two million times and was one of TED’s top 10 ideas of 2015.