Written by Savannah Sobrevilla

I can’t say I’ve always loved being Peruvian. It was hard to get past the rotisserie guinea pigs and corn of it all. But I can say with complete certainty that I’m obsessed with it now, corn and all. It isn’t until you’re older that you realize your parents have great taste in music. Or that being rich in culture is a privilege, though I can imagine it may not feel that way for people who don’t like their culture and whose culture doesn’t like them either.

Personally, I never liked the music I’d hear at family gatherings. It made me feel like an old woman. Not even an old woman, a doña, which somehow felt worse because doñas kiss you too hard, insist your name is Sabrina, and wipe their lipstick off your cheek with spit that smells like papaya, Tums, and cortado.

When you’re 11, you don’t want to feel like a doña. At least I didn’t want to feel like a doña. What I really wanted was to blend in, to be as unremarkable as a linoleum floor, to look like any other of the girls in my grade—most of whom were Cuban. Their jet-black hair had volume and loads of life and their skin was white like porcelain yet sunburn-proof. Their accents were saucy and sounded like my teachers. Their culture had guava and cheese pastries and yuca fries and they had superstars like Celia Cruz and Gloria Estefan on the radio. Like, how cool is that? Though I embrace Cuban culture and adore it because it sounds like home, it’s ultimately not mine.

Growing up, I ran away from Peruvian culture. In the context of my childhood, it didn’t mean sexy like Peruvian-American actor Benjamin Bratt, it meant archeological like National Geographic. When you’re trying to be Avril Lavigne and Britney Spears, your proximity to indigenous cultures seems to be the only thing keeping you from doing so. The contrast between their hot punk/pop sound and the tukituki-sounding music and smell of the corn juice (chicha morada) that my culture is known for, made me want to scream.

Suffice it to say, I didn’t like being Peruvian but I’m lucky because my parents love being Peruvian. They never encouraged me to assimilate and made it clear that being Peruvian is a great thing to be. “Over 4000 varieties of potatoes!” my Abuelo Wicho would remind me during my visits to Lima, “Why do you think the French fries are better here?” It landed on deaf ears for years, until I got really into Cartola and Elis Regina, Brazilian artists. They’re the kind of artists non-Latinx people use for the love-sick sequences in their indie movies. Since I’ve always liked older music more than modern music, it made sense that my foray into Latinx music would follow that tendency.

I love that old Brazilian music is a reliable crowd-pleaser. Regardless of the setting or group, no one will shut down bossa nova out of fear that they may come off as ignorant or intolerant. Playing “Aguas de Marco” on repeat was a musical test of sorts for myself and the people around me. “I love this type of music,” they’d say, and I agreed, some of the best sounds in the world come from beautiful Brazil.

Up until a little too recently, music historians have credited The Sex Pistols with starting the punk movement in 1975, however, Los Saicos released their first album in 1964—making them punk pioneers.

Up until 2 years ago, my most liked Spotify playlist was “Samba Baby”, racking up 7 cherished likes. “Samba Baby” spent years becoming what it is, compiled of songs found on Spotify and in Wikipedia holes. I still love listening to it. Cartola’s simplicity and soul make me tear up. I think it’s sweet that Brazilians love their country so much that they created songs like “Samba Da Minha Terra” and “Aquarela do Brazil” to honor it.

Still, Brazilian music isn’t my culture (it’s not even in Spanish), but I was getting warmer. It was “Café” by Eddie Palmieri and Ismael Quintana that started my love of music whose lyrics my parents and I could understand. “Café” is undeniably sexy—the sax, the percussions, the piano, the way you can’t help but find a beat and dance to it. It’s smooth, delicious, and juicy. But more impactful than the rhythms were the lyrics. Simple: Café, tosta’o y cola’o. “Coffee, roasted and brewed,” said in an accent familiar to me. Something clicked.

Growing up, I ran away from Peruvian culture. In the context of my childhood, it didn’t mean sexy like Peruvian-American actor Benjamin Bratt, it meant archeological like National Geographic.

Of course, I grew up listening to divas like Shakira, Thalía, and Paulina Rubio. In fact, I had a 3-foot-tall poster of Shakira wearing low-rise, lace-up leather pants and a barely-there silver bra top. (If you had this poster I bet you’re gay, too.) I had Latina icons, but for some reason, I never connected them with my “Latinidad.” I’m not entirely sure I had even been made aware of my Latinidad by that time, which is why my love for them felt so unfettered, so pure. Everyone around me listened to Shakira, spoke Spanish, and ate media noches. From my perspective, Laundry Service wasn’t any more targeted to a certain group than it was for me.

“Gritos sin Querer” is the first playlist I dedicated to just Latinx music. It’s filled with the likes of Chavela Vargas, La Lupe, Celia Cruz, and Eliades Ochoa. Around this time, I stumbled upon Sexographies, a book of essays by Gabriela Wiener, an author who is not only Peruvian but also a queer woman.

Representation matters–we hear it all the time, but we never fully understand it until we see ourselves in a work of art for the first time—not dissimilar from lesbians needing to suffer a 3-hour long period film for a kiss and a single finger caress to realize we’re starved for media. Sexographies made me feel seen and connected to a community I didn’t know I was missing. Las cholas y tortilleras.

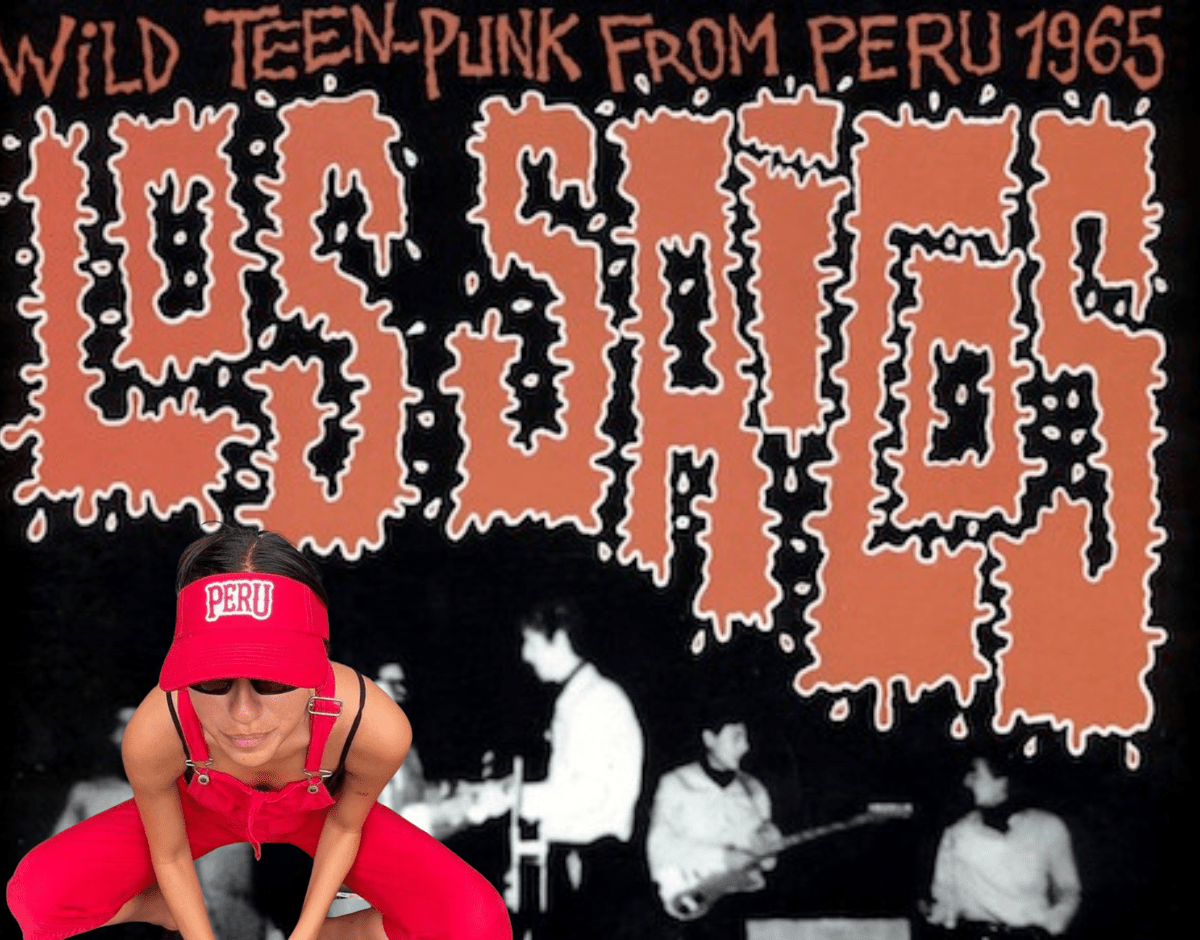

While building my “Gritos sin Querer” playlist, I let Spotify’s recommendations take over after the playlist had gone through all of its songs. I suppose I had grown used to salsa and merengue, because when I heard the screams at the beginning of “Camisa de Fuerza”, I was caught completely off guard. The next song, “Demolición”, was even rowdier. I had struck gold. It was punk. Peruvian punk. From a band called Los Saicos, which couldn’t be a more culturally-appropriate name since Peruvians love to phonetically write out English words and then use them ironically (The Psychos = Los Saicos).

Up until a little too recently, music historians have credited The Sex Pistols with starting the punk movement in 1975, however, Los Saicos released their first album in 1964—making them punk pioneers.

That’s so badass.

About the Author:

Savannah (or Sav) Sobrevilla was born and raised in none other than the 305. She studied nowhere and lives in the Lower East Side while daylighting as a fashion person. Her writing is at the intersection of satire, spiced-up melancholy, gay stuff, and fashion. Typically, you can find her jogging around Chinatown and trying to hold it together.

Follow Sav here: www.instagram.com/savsob